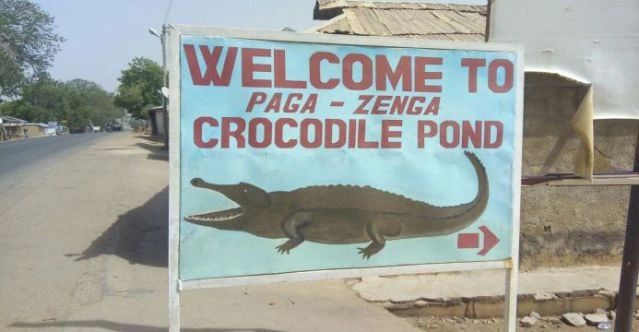

In a world where human-wildlife conflict dominates conservation headlines, one community in northern Ghana has maintained an extraordinary relationship with one of nature’s most formidable predators for over six centuries. The Paga Crocodile Pond, located in the Upper East Region of Ghana, stands as a living testament to the power of cultural reverence, spiritual belief, and the possibility of peaceful coexistence between humans and wildlife.

A Sacred Heritage Spanning Six Centuries

The Paga Crocodile Pond has been venerated as sacred ground for approximately 600 years, with its origins rooted in legends that continue to shape the community’s relationship with these ancient reptiles. The pond is not merely a tourist attraction or ecological site; it represents a profound spiritual connection between the people of Paga and the crocodiles that inhabit its waters.

According to local oral tradition, the sacred status of the pond traces back to a moment of salvation. One account tells of a dying man who was led to the water’s edge by a crocodile. Upon drinking from the pond, the man’s life was spared. In gratitude, he declared the pond sacred and established a covenant that no crocodile should ever be harmed. Another narrative speaks of a crocodile that rescued a man from a lion’s attack, with the grateful survivor pledging eternal protection for the crocodiles and their descendants in return.

These foundational stories, passed down through generations, have established an unbreakable bond between the community and the crocodiles—a relationship built not on dominance or fear, but on mutual respect and spiritual kinship.

An Unprecedented Safety Record

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Paga Crocodile Pond is its perfect safety record. Despite the inherent danger associated with crocodiles elsewhere in the world, no human fatality has ever been recorded at this sacred site. This extraordinary fact defies conventional understanding of crocodile behavior and challenges assumptions about human-wildlife interaction.

Children swim in the same waters where dozens of crocodiles reside. Visitors sit beside these powerful reptiles for photographs. The crocodiles respond to the calls of local guides and approach humans with a calmness that would be unthinkable in virtually any other setting. This peaceful coexistence exists not because the crocodiles have been domesticated or trained—they remain wild animals—but because they are treated with unwavering respect and reverence.

The Spiritual Dimension

The relationship between Paga’s residents and the crocodiles extends into the metaphysical realm. The community maintains a deeply held belief that the crocodiles embody the spirits of their ancestors, serving as a living link between the earthly world and the afterlife. This spiritual connection manifests in observable patterns that reinforce the community’s faith: when an important community member passes away, locals report that a crocodile dies around the same time, a phenomenon interpreted as evidence of the intertwined destinies of humans and reptiles in Paga.

This ancestral connection elevates the crocodiles from mere wildlife to sacred beings deserving of protection and honor. The pond itself is considered hallowed ground, and the prohibition against harming or consuming crocodiles is not simply a conservation measure but a fundamental taboo carrying serious spiritual consequences. Violations of this sacred law are believed to bring generational curses upon the offender and their descendants—a deterrent far more powerful than any legal penalty.

Cultural Preservation in Modern Times

In an era of rapid modernization and environmental degradation, Paga Crocodile Pond represents a successful model of indigenous conservation rooted in cultural tradition. The site demonstrates how traditional ecological knowledge and spiritual beliefs can achieve conservation outcomes that modern approaches sometimes struggle to accomplish.

The pond has become an important cultural heritage site and tourist destination, drawing visitors from across Ghana and around the world who come to witness this unique relationship firsthand. Yet it remains fundamentally a sacred space for the people of Paga, where ancient covenants are honored and the boundary between human and animal, living and ancestral, becomes beautifully blurred.

Conclusion

The Paga Crocodile Pond transcends simple categorization as either a wildlife sanctuary or tourist attraction. It is a place where history, spirituality, and nature converge—where wild crocodiles treat humans like family because six centuries of respect have earned that trust. In the waters of this sacred pond, the people of Paga have preserved something increasingly rare in our modern world: proof that humans and predators can share space not through domination, but through reverence, reciprocity, and recognition of our shared place in the natural order.

As conservation challenges intensify globally, perhaps the lessons of Paga—where protection flows from spiritual connection rather than legal enforcement, and where wildlife thrives because it is honored rather than controlled—offer wisdom worth heeding far beyond the borders of Ghana’s Upper East Region.